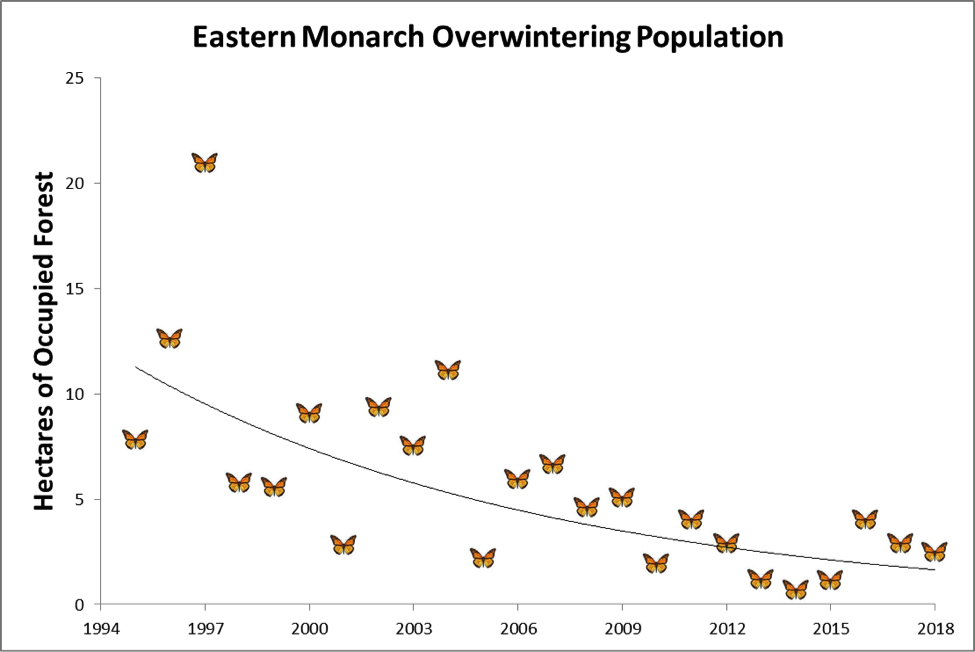

Summer vacation in elementary school meant humid evenings at the local park, picking and tasting sour berries from random trees, and endless efforts to capture an intricately patterned monarch butterfly. Monarch butterflies were everywhere, but now I can’t recall the last time I saw one. These butterflies are being closely monitored by the US Wildlife and Fish Service to determine whether the species warrants federal protection and the conservation status of ‘endangered’.

The Center for Biological Diversity released a notice describing exactly how dire the monarch situation is, reporting that in the mid-1990s the monarch “population was estimated at nearly one billion butterflies, but this year’s population is down to approximately 93 million butterflies.” That is a 91% drop in population size in only two decades, and if you love to eat, you should be worried.

Monarch butterflies are pollinators—organisms that facilitate reproduction in one-third of all crops by allowing the spread of seeds and the flowering of fruits. Without pollinators, we would face drastic food shortages with grains as our only food source.

Brazil is already facing the financial consequences of a crop shortage due to dwindling numbers of pollinator species, with an estimated decline of agricultural contribution to the GDP of 6.46-19.36%, resulting in a net loss of 4.86 to 14.56 billion dollars per year. Regardless of the course of our past actions, we must closely examine the environmental and anthropogenic roots of this issue—climate change, loss of habitats, and pesticide usage—to effectively identify a solution.

Environmental issues like climate change have influenced the migration and breeding patterns of butterflies. Monarchs migrate to Mexico or Southern California for the winter, and travel back to the Northeast to lay eggs which hatch, undergo metamorphosis, and cycle through four generations over the summer months.

Inconsistent temperatures have created existential problems for monarch butterflies, who have been observed migrating to the Northeast both too early in the season, and too late. When the butterflies are too early, they end up without plants to lay their eggs. Too late, and they face harsh winters. What’s more, the increase in severe weather conditions such as droughts and storms have killed millions of butterflies at a time.

Anthropogenic developments have contributed to this rapid decline too. Acres of land in Mexico have been deforested for housing developments, resulting in a loss of overwintering spots for

monarchs to nest and breed. According to the World Wildlife Fund, of the 49.17 acres of breeding grounds, “47.27 or 96% were affected by large-scale illegal logging”.

In addition to the low count of monarch communities that have survived erratic migration conditions and a lack of proper habitats for breeding, monarchs return to the US find a new problem: a dearth of milkweed crops to lay their eggs.

Agricultural habits in the Midwest have led to a proliferation of GMO crops that require pesticides to be managed. However, these pesticides kill all weeds, including milkweed, and are used indiscriminately. Excessive pesticide use has resulted in widespread extermination of habitats and limited food availability for the lucky caterpillars that do hatch.

The monarch butterflies will not be able to make a comeback until we make serious lifestyle changes. Expectations are high for the upcoming decision by the US Wildlife and Fish Service in June 2019regarding the protection of monarchs from further harm. Until then, we must do our part to rescue the monarchs by planting milkweed, butterfly bushes, cosmos, zinnias, dill, fennel, and more in our backyards.

Monarch population graph courtesy Center for Biological Diversity