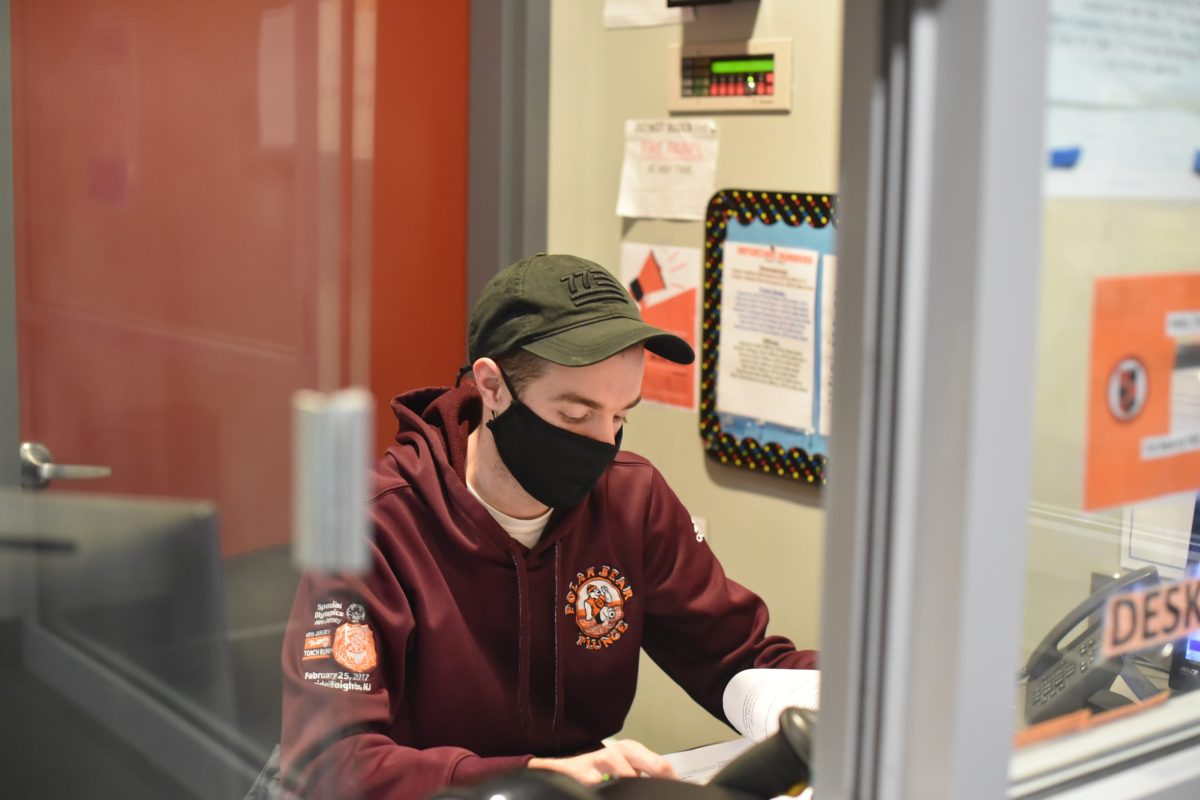

Contrary to popular belief, NJIT does recycle. These efforts are led by Charlie Nieves, the Director of Building Services, and Henry Rzemieniewski, the Manager of Custodial Services. It is their job to take waste that is generated on campus each day to a facility a few blocks from campus, at 125 Newark Street.

The Lowdown

At the facilities building, a team of about seven custodial employees at a time sort through the day’s collection and extract recyclables like soda cans from the waste stream.

“You don’t see what we’re doing because we don’t want you to see it,” Nieves explains. “We don’t want you to see garbage bags laying around or garbage containers all over campus.”

They do it because they want the campus to look good. “Trust me, we are recycling and we’re trying to increase those numbers. We’d like to show the students our numbers and share the progress we’ve made.”

The numbers are good but not great.

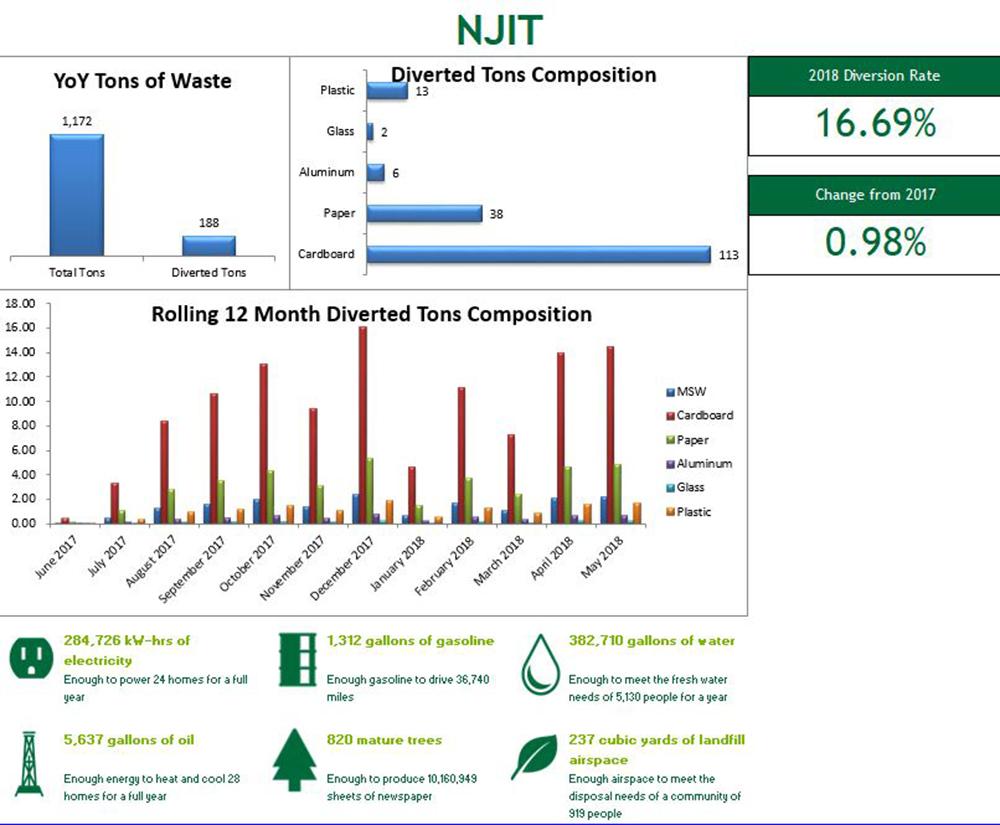

Out of a total 1,172 tons of waste collected in 2018, 188 tons—or 16.69 percent—were deemed recyclable, and therefore diverted from landfills, according NJIT’s June 2017-May 2018 Waste Report from Waste Management. This is a 0.98% increase from the previous academic year’s recycled waste.

So, what might account for the differences?

Rzemieniewski said students are not separating recyclables from their regular trash. While his team is trained in properly sorting recyclables and always look for ways to salvage recyclables in the trash, they can’t force the campus community to pay attention to where they toss their garbage. Training his team took time, but now “it’s about changing the culture of the people putting stuff in the trash.”

His comments were echoed by Andrew Christ, the vice president for real estate development at NJIT. Christ concedes that “we have improved our diversion rates but can certainly do better.”

Recycling bins on campus are “single stream”, meaning they include plastic, aluminum, and cardboard.

The Numbers

In 2017-18, the majority of NJIT’s recycled product was cardboard, making up about 60% of all recyclables by weight, according to the NJIT Waste Management report. In contrast, plastic, glass, and aluminum make up less than 12% by weight of all collected recyclables, or 1.8% of all trash.

Rzemieniewski assessed that the plastic, glass, and aluminum sector make up such a small percentage because it is lighter by nature, but also people are likely putting their trash in the wrong bins. Cardboard, on the other hand, is recycled by default, “It’s harder to try to throw cardboard in the garbage,’’ he said. “It just gets recycled when it’s done.”

Rzemieniewski came to NJIT after working at MetLife stadium, where he focused on making sporting events more sustainable by collecting recyclables in the stands during events and sorting through the garbage with a team in the days following the events. Over the course of his time at MetLife, landfill diversion rates increased from 20% to over 65%, he said.

The job was not without its frustrations, especially since the audience was composed of temporary, intoxicated, singularly-focused fans. “I put rubber traps above recycling bins [so that] you really had to push down to fit trash in the recycling bins. I witnessed fans trying to stuff things that blatantly didn’t fit in there. The culture in this area is a problem.”

The Culture

NJIT, in contrast, has the advantage of being a steady community. “You can get buy-in from the students and change the culture,” Rzemieniewski explained. A shift in culture is a major requirement in increasing recycling numbers. The campus center and residence halls are hotspots for regular traffic and food waste/recyclables.

Here at NJIT, one of Rzemieniewski’s biggest challenges is the misuse of public receptacles.

Without user compliance, a lot of time is spent sorting and recovering recyclables behind the scenes.

“We have the manpower to do whatever we can possibly do. If there’s a bag of about 60%-70% recycling, we’ll open it up and recycle what we can. But of course, if it’s one can in a bag of trash, we have to let it go. It’s just not feasible. We do what we can to keep our numbers up, and so far, we’ve been really successful, and there’s only more opportunities to keep doing that,” Rzemieniewski explained.

“Your choice to recycle or not has an impact on our environment.”

But the biggest problem with recycling disposal according to Rzemieniewski, is “what China will take and what China won’t take.” Since China recently refused to accept most of other countries’ trash and recyclables, recycling guidelines have become more stringent. The bottleneck effects of this new policy have been seen on a local level. “We had an issue a couple months ago where we got held up here because landfills in Pennsylvania were having issues.” Rzemieniewski said.

Since such concerns do not affect the daily life of average Americans, it is easy to develop a culture of apathy regarding individual waste. “‘I’m just going to throw this wherever I want because, guess what, it’s going to go away,’” Nieves says, mirroring the general public’s sentiment about garbage. “‘The garbage is going to be collected, it’s going to disappear and it’s not going to be my issue anymore.’ We have to start showing people that, yes, it is [your issue]! It’s going into, for example, water streams and destroying ecosystems.”

Anyone can take part in sustainability initiatives, such as making recycling the norm on campus, whether or not they identify as an “environmentalist” or “tree hugger.” For Rzemieniewski it is very personal. “I have 8-year-old twins at home, and that’s why I do this,” he said. “I care. I really want to make a difference.”

Your choice to recycle or not “has an impact on our environment,’’ Nieves added. “Your friends, your family are living in that environment,’’ he said. “You choose what you want for your future.”