“How do you want us to pose with this?” Mykelti Thomas, president of NJIT’s Theta Chi chapter asked. Together, he and a fellow brother solemnly held up a water filter they had recently purchased for their frat house.

This was not the kind of shopping Thomas had expected to be doing upon his return to NJIT this fall. But it has become part of the “new normal’’ for Thomas and his fraternity brothers, given that their off-campus frat house is located in the section of the city served by the troubled Pequannock water system.

The problem revolves around a water chemistry issue that most people have probably never heard of: anti-corrosion chemicals, which are used to prevent lead in underground pipes (known as lead-service lines) from leaching into homes.

In the case of the Pequannock water plant of the Newark Watershed, an engineering study that was completed last October found that those chemicals have stopped working, and even though the city has started using new anti-corrosives at the plant, it takes time for the new chemicals to take effect.

So in the meantime, the problem persists. In all, the problem has impacted about 18,000 one- and two-family Newark homes – or about 25 percent of all residences – that are served by the Pequannock water system, according to data cited by Newark Mayor Ras Baraka during an interview this past week on the television program, Democracy Now.

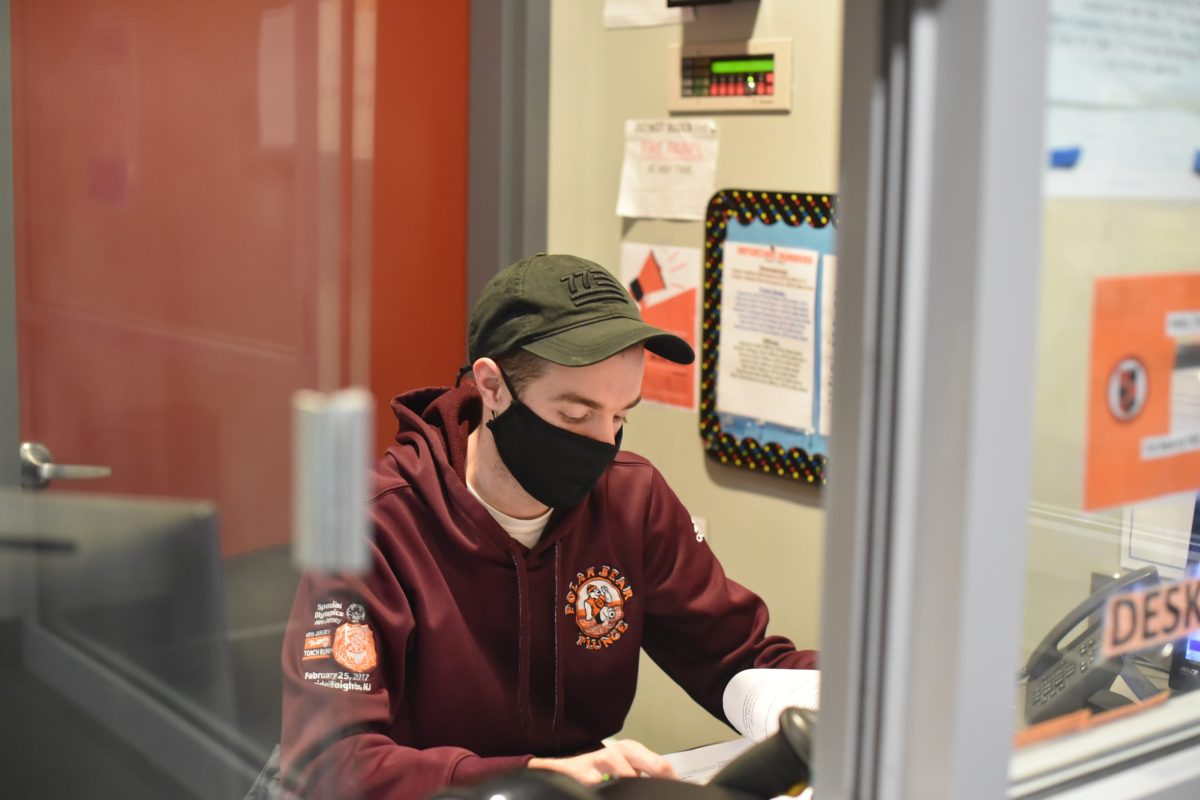

Thomas takes visitors to talk with fellow fraternity brother Mike Lukijaniuk, a third-year Information Technology student. Lukijaniuk settles down in his seat while to his left, the Theta Chi banner hangs proudly in his room. He recounts that after hearing about Newark’s lead water crisis on the news this past August, three of the brothers drove to a BJ’s Wholesale Club and walked out with 13 cases of bottled water between them. “We even use bottled water to brush our teeth,” he reveals. All of their showerheads have water filters installed on them.

Next is a stop at Theta Chi’s first-floor bathroom sink. There’s this one faucet, Thomas says, that began emitting brown water in August. He put an empty plastic bottle under the faucet, and sure enough, it filled up with brown water. Thomas says he’s not sure if the brown water is related to the lead issue, but he’s reported it to the landlord.

Nor is Theta Chi the only NJIT fraternity struggling to take protective measures against possible lead-water exposure. In all, at least 60 NJIT students live in eight privately owned off-campus fraternity houses on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard’s “frat row.’’ But every weekend, hundreds of NJIT students attend frat house parties, which means the number of people potentially impacted by the water situation is significantly larger.

Earlier this semester, three Theta Chi brothers drove to a BJ’s Wholesale Club and walked out with 13 cases bottled water between them.

The water problems have changed the rhythms of off-campus fraternity life. For example, at Alpha Phi Delta, a fraternity that is not affiliated with NJIT but nonetheless houses NJIT students, chapter president and fourth-year Business major Corbin Dix, said his Alpha Phi Delta brothers are relying on bottled water.

“Alpha Phi Delta is still doing everything we can to provide a safe environment for our classmates when they do come to socialize,’’ he said. “We’ll be going out of our way to buy as much bottled water as we need this semester one way or another for our events”

And at Tau Kappa Epsilon, chapter president Sam Abraham, a fifth-year Mathematics and Computer Science major, said that even though the city provided the fraternity with water filters in mid-February, he and his housemates have only used bottled water since returning to campus this fall. “We are avoiding using the tap lines for anything now,” he said. The brothers in the fraternity house spend about $50-60 a month on water, he said.

So how much lead is in the water?

That’s a harder question to answer than one might think.

Because lead generally enters the drinking supply in the last 200 feet of its journey from source to a resident’s home, the only way a water system can check for lead in drinking water is by asking residents to collect water samples from the tap in their homes. The process involves following certain protocols and then having those samples tested for lead at a certified laboratory.

In the case of Theta Chi and the other MLK fraternities, what puts them at risk for lead is their location – they are served by the Pequannock service area – and the existence of a lead-service line connecting the houses to the water main on the street.

That information is publicly available, thanks to the city’s online inventory of lead service lines. When The Vector entered the addresses of the eight NJIT frat houses into the database, it confirmed that all eight of them were in the Pequannock service area and had lead-service lines.

But whether all of that translates to high lead levels in the tap water at places like Theta Chi is not known. Hopefully, however, the data will come soon.

In a Sept. 27 email response to a query from The Vector, Jim Krucher, the director of Fraternity and Sorority Life, said he reached out to the alumni representatives for all the fraternities that rent or own houses in the MLK neighborhood. Krucher asked them if the tap water in their houses had been tested for lead, and if so, when the last test was performed and what the numbers were.

He added: “We are waiting for test results before we develop a plan of action. In the mean-time, NJIT [Office of] Student Life is currently supplying bottled water to all NJIT Fraternities in the MLK neighborhood.”

Thomas, the president of Theta Chi, said his fraternity received their water on Sept. 24.

So how is lead getting into Newark’s water?

Newark’s lead-water crisis stems not from the water source – in the case of the Pequannock water system, that’s the Pequannock Watershed in West Milford – but rather with the aging underground pipes that connect individual homes to the city’s water main.

At the time these pipes were installed, many of these service lines were made out of lead. That is a big part of the problem: over time, these pipes corrode, causing lead to leach into the water. (This is not unique to Newark: millions of homes across the United States had lead-service lines.)

To offset this problem, water utilities often add anti-corrosion chemicals to water before it leaves the water treatment plant in order to form a coating inside the pipes to keep them from corroding.

How the problem emerged

In Newark’s case, problems with the city’s water supply started to emerge in 2017, after the state Department of Environmental Protection tightened up its drinking water sampling rules. The change was prompted after 30 public schools were disconnected from the city’s water supply because of elevated levels of lead in their water fountains, water faucets and other water.

For the last two years, those sampling studies have found that more than 10 percent of the homes in Newark had lead levels higher than 15 parts per billion, triggering what is known as a “lead action exceedance’’ and a notice of non-compliance from the state Department of Environmental Protection (NJ DEP). These results from twice-yearly reports are posted on the NJ DEP’s website.

October 2018: turning point

But in October 2018, an engineering study by CDM Smith concluded the problem stemmed from the anti-corrosion methods being used at the Pequannock Water Treatment plant. The chemicals were no longer working.

That CDM Smith report prompted the city to begin distributing water filters to residents in sections of the city served by the Pequannock water system.

The city then ramped up its response again this past August, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ordered the city to begin distributing free bottled water to residents in the Pequannock area after preliminary tests of three water filters seemed to suggest that the filters weren’t working. That initial analysis has been offset by additional testing that was completed last week, which found that water filters are 97 percent effective when used properly.

Given this news, the city decided on Oct. 7 to end its free water distribution to all but pregnant women and families with children under the age of six.

What’s next?

The water-filter program is only a short-term solution. The city is on track to replace all 18,000 lead-service lines in the Pequannock water district in the next two years to 30 months, which, the city says, is the long-term solution to solving the problem.

In addition, it began using new anti-corrosion chemicals at the Pequannock plant in May. At a Town Hall for Newark residents this week, Mayor Ras Baraka said the new chemicals are “getting into the system,’’ but the city won’t be able to say that the city’s numbers are below the lead-exceedance levels until the city successfully completes two rounds of its required 6-month testing cycles. However, he said, city officials are hopeful that there will be a “dramatic impact’’ by the end of the year.

“We are avoiding using the tap lines for anything now.”

Sam Abraham, TKE President

In all, at least 60 NJIT students live in eight NJIT off-campus fraternity houses on Martin Luther King Boulevard’s “frat row.” But every weekend, hundreds of NJIT students attend frat house parties, which means the number of people potentially impacted by the water situation is significantly larger.

P

Pictured above: Screenshots from Newark’s Check My Address site, which allows users to look up their address in city records and to learn whether they are served by a lead service line and whether they are eligible for an NSF Certified Filter. Data from this website indicates that all eight off-campus fraternities have lead service lines. This means they are at risk for lead in their water.

How to find out if you have a lead service line:

- Go to the website: https://newarkleadserviceline.com/check-your-address

- Type in your address: In the upper right corner of the “Water Account Lookup” map, type your address into the search bar.

- Read the information provided: After searching up the desired address, a blue dot will indicate the location and an information text book which will provide any information regarding which service line the address is connected to as well as recommendations as to whether or not individuals living at that address should get water filters and/or water bottles.

Editor-in-Chief Carmel Rafalowsky and Managing Editor Daniil Ivanov contributed writing.

Photos by Photographer Editor Katherine Ji and Business Manager Regee Lozada

Layout design by Executive Editor Sandra Raju

This story is part of our participation in a statewide climate reporting collaboration with members of the NJ College News Commons, a network of campus media outlets working together to cover the climate crisis in New Jersey.