The Newark Museum of Art is currently displaying “Norman Bluhm: Metamorphasis.” Bluhm (1921-1999) is a historically underrated artist, and the Newark Museum of Art has collected a large selection of his work, with some pieces which they have already owned along with many pieces that have been loaned from private collections and museums, to showcase his artistic progression throughout life.

The exhibit is curated by Tricia Laughlin Bloom, the Newark Museum of Art’s curator for American art, and guest curated by Jay Grimm, a close friend of Norman Bluhm. When creating the exhibit, Bloom and Grimm decided to take a more holistic approach, covering all periods of Bluhm’s life as an artist, unlike most exhibits that focus on a specific period of his artwork.

Bloom spoke briefly on the museum’s decision to highlight Bluhm in such a way. “Some people say like, well how did you pick this person? Why is he so special that he gets a big one-person show? Part of it is when we have a major work in the collection that we want to kind of revisit, and in the case of Norman Bloom, the fact that he hadn’t had a big museum show since the 1970s. I mean, there’ve been small shows that look at just the early work or just the late work, but we thought it was really worth it to be able, for people to be able to see the early, the middle, the late and the end together.”

Grimm started off the tour of the gallery elaborating on Bluhm’s upbringing, which would influence his unique artistic style later in his life. As a child, “his father was traveling on business and doing big civil engineering projects in Russia, and so Norman was fluent in Italian and had this real exposure to the old world — the classical world. He was always interested in that.”

Bluhm would then move to Chicago in his later teens. “He was a student of Mies van der Rohe — an architect student in Chicago. Mies and the Bauhaus [a German art school] had fled Nazi Germany and Mies ended up teaching him…. Norman was a very young student of his then went to serve in World War II and then came back to Chicago.”

“His mindset had changed,” Grimm continued, referring to Bluhm’s post-war life. “He wasn’t ever really in architecture. And then using GI Bill money, he moved to Paris, and there he married a French woman. So, unlike a lot of expressionist artists in Paris after World War II, he had a much deeper connection to that area and also became French.”

In most of his earliest works, Bluhm painted in a French impressionist style, using brush strokes to paint realistic Manet and Monet inspired paintings of landscapes portraying events in real life. The curators put on display a single piece of art from this early period in order to contrast with the more abstract artworks in the rest of the exhibit.

In 1956, Bluhm’s marriage broke up and he moved to New York City, where a thriving expressionist art scene awaited him. “So in New York,” Bloom explained, “he starts working much larger, you see these really big bold canvases. This is of course a moment, just in the wake of Jackson Pollock working on mural-size scale, where the whole New York school [was] kind of getting international attention for working big.”

Throughout his career, Bluhm would continue to adapt his art style, moving to Pollock-style “masculine” pieces with sharp corners and jagged edges in an expressive way that captures movement on a still canvas. He then began exploring curvature and feminine forms, in the meantime becoming acquaintances with various artists and poets—including Newark’s own Amiri Baraka—whom he would collaborate with. An entire wall is displayed of a set of paintings with poems written within them.

Despite his changing artistic image, Bluhm always kept to his classically trained roots. As Grimm puts it, “It’s a little different. Norman always painted on an easel or on the wall so you can see the drips coming down. He always used a brush. So, even in his most abstract expressionist phase, he was still this kind of, what he called a ‘romantic painter’ and by that he meant connected to the French tradition.”

“And throughout his career,” continued Grimm, “because this is such an engaging painting or type of painting… he was always considered an abstract expressionist. And I think, and so does Tricia, that that kind of confuses our understanding of him because he had this decade in Paris where he really formed himself as an artist.”

“It’s worth noting,” Bloom said, “that because of this very kind of traditional training that Norman had, he was working from a live model and doing figure studies from the very beginning, you see an example on that early wall. And he would do it regularly. Even when he was working completely abstract, he was still making numerous rapid paintings with a live model in the studio.”

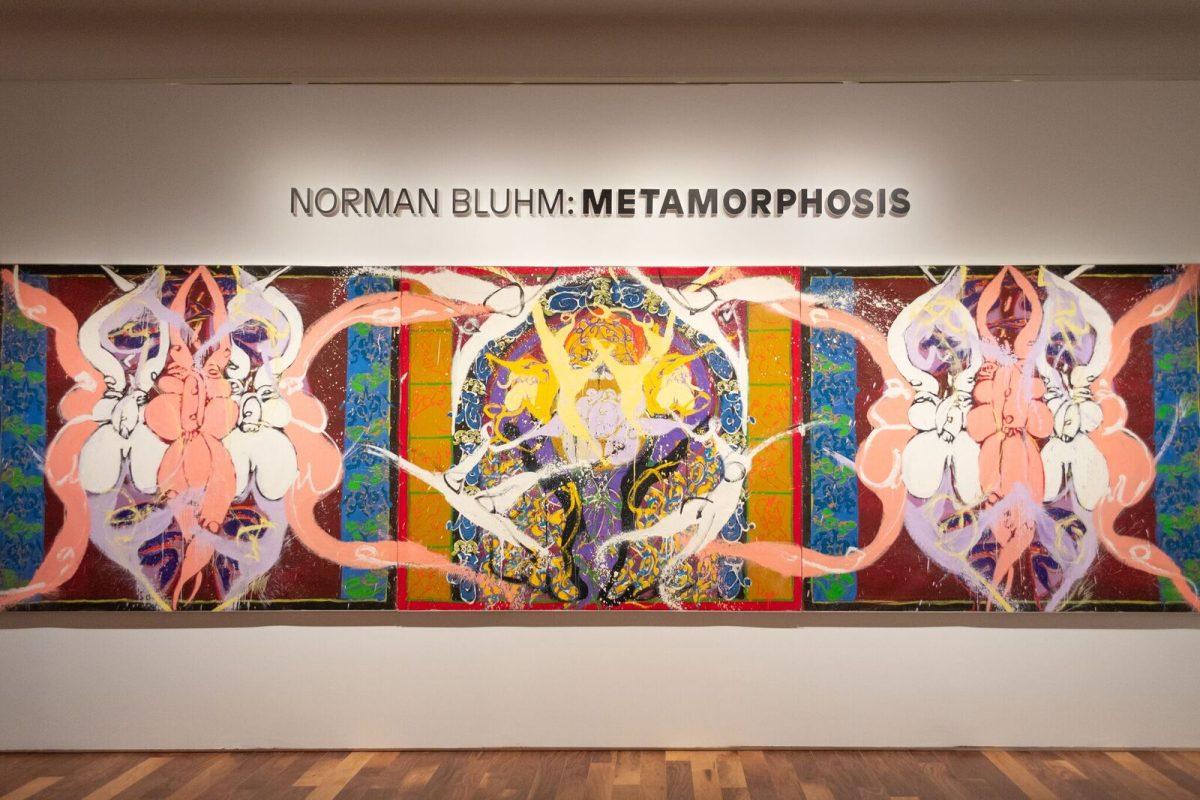

In the late years of his life, Bluhm began painting monolithic triptychs as seen in a couple of his last and largest artworks “Eye of Salonica ” and “Persephone,” which he completed in 1998 and 1995, respectively. Generally, triptychs are classical Christian paintings used in order to portray religious beliefs and events. The basis of his late works on this classical style shows his deep connection to the upbringing. However, Bluhm did branch out and combine this classical style with the expressionist style that he used for most of his life, creating a unique mixture that is rarely, if at all, seen elsewhere in the works of other artists.

In the pieces from this period of his life, Bluhm heavily included symmetry in his artwork. In each of these pieces, the first and last thirds are almost identical while the middle third contrasts with a clash in colors and design.

In “Persephone,” Bluhm uses more soothing and nurturing colors, specifically the lavender, in order to display the feeling of comfort and love. The addition of what seems to be little nests of geese protected by the adult geese towards the bottom of these thirds gives a loving tone to the artwork. However, the middle panel displays a deadly and gloomy tone through the use of the dark blue as a major color in the section and the display of geese huddling in fear from the darkness. The order of these sections can be interpreted as a sequence of life, death and rebirth.

However, despite this symmetry, it is very noticeable that the painting is not perfectly symmetrical. As identical as the two thirds may be, there are distinct differences such as the size of the white oval at the top of the thirds on the ends or the difference in line thickness on one half compared to the other. This serves to show that although there is an underlying cycle that may repeat itself, each repetition will never be exactly identical between occurrences.

This also connects back to Greek mythology as well, seen in the name of the artwork. Persephone is known to be the god of vegetation or plants. As a result, she is also in control of all of the seasons. Therefore the thirds can also be interpreted as the cycle between summer, winter and summer again. Likewise, the gallery itself is cyclical, taking the viewer around the circular gallery and through Bluhm’s life.

These same concepts can be identified in “Eye of Salonica” as well. The thirds are ordered in the same manner of life, death and rebirth as seen in “Persephone.” Although the lighter color of yellow as opposed to red in the middle third may hint that this is the third representing life, the explosive manner in which the paint is seen creates a continuation of the same concepts that are seen in “Persephone.”

Bluhm has not been given much of a spotlight throughout art history, but the Newark Museum of Art has decided to change that. “Norman Bluhm: Metamorphosis” will be displayed until May 3.

Photos by Birju Dhaduk