Disclaimer: All of the following works in this article are unedited submissions to The Vector’s Fall 2024 Writing Competition. The content of these works does not reflect the views of The NJIT Vector.

WINNER

The Sock Pile: A Transition to Adult Life

by Marcus Hilario

The sock pile is a staple element of most dorm laundry rooms. Whether you forget a sock in the bottom crevice of the drum, or catch someone else’s garments in your freshly cleaned laundry, these abandoned foot gloves can add up fast. What starts out as a single lost piece of nylon on the top of the dryer slowly adds up over the course of the semester to form the behemoth of a pile every dormer has come to know and love. These unclaimed socks remain on top of the laundry machines waiting for the day their owners return, with a shrinking hope that one day they will be reunited with their partner and safely tucked away in a bedside drawer.

However, this recurring phenomenon raises a few burning questions: Why are so many socks left behind? Why does nobody claim them? What happens to these lost garments at the end of the year? Is this a universal experience for all residents at NJIT, or just an unlucky batch of floormates?

Thankfully, one bored student journalist had a free weekend.

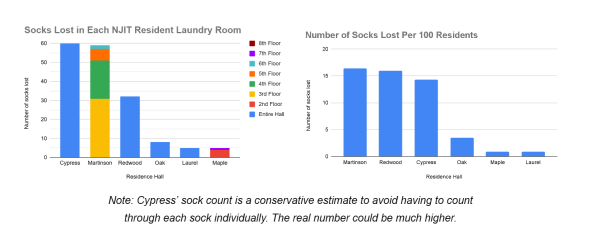

A visual survey of each residence hall laundry room was conducted last October 27, and shows a breakdown of all 169 lost socks in each of the six residence halls. Socks were counted whether they were on top of the machines or lying on the floor.

Note: Cypress’ sock count is a conservative estimate to avoid having to count through each sock individually. The real number could be much higher.

The data suggests that the sock pile experience may not be universal across all residence halls in NJIT. Underclassmen dorms such as Cypress, Redwood, and Martinson have significantly higher sock buildup than their upperclassmen counterparts in Oak, Laurel, and Maple even after the number of residents in each building were taken into account.

This trend is likely not a coincidence, but an indicator of the hurdles that come with living alone for the first time. Any new environment takes time to adjust to, and it seems that the weekly activity of keeping laundry in check is no different. From forgetting to double check the dryer, to accidentally dropping your clothes on the way out, there could be a multitude of reasons for the sock pile’s ever-increasing size.

Fortunately, for those frustrated by a lack of cleanliness and organization, you can rest easy knowing that there will be minimal sock accumulation in the upcoming years. It seems that through one way or another, dormers are able to develop better laundry-checking habits by their junior and senior years.

However, regardless of whether or not first-year adjustments are a valid excuse, over 500 more socks will join the pile by the end of the academic year based on current trends. If brought straight to the dumpster, this would be around 70 more pounds of otherwise perfectly usable clothing added to the 11.3 million tons of textile waste sent to US landfills yearly.

Luckily, according to the Office of Residence Life, all clothing items left behind are donated to NJIT’s Career Closet or other local companies at the end of the year, where they can find a new and hopefully more attentive owner. However, regardless of where your socks end up, it is still a good practice to double check for any left-behind clothes before you leave the laundry room. Not only does it create a better laundry experience for your fellow dorm mates, it builds better practices for your future adult life, preventing you from being responsible for that one lost sock on the 7th floor of Maple Hall.

As it stands, the sock pile symbolizes a period of adjustment for first-year dormers adjusting to adult life. As young adults entering a world full of responsibilities, minor mishaps are bound to happen. But no matter how chaotic and messy the laundry rooms may be right now, every lost sock added to the pile is another opportunity to learn and grow from.

HONORABLE MENTION

Echoes of Ancestry: The Fight to Preserve the Philippines’ Indigenous Languages

by Arhan Shukul

In a small classroom deep in Northern Luzon’s mountainous core, the cadence of an ancient language echoes. Children parrot phrases in Kankanaey, an indigenous language spoken fluently by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly elders. Alon Gardo teaches these children to talk as their forefathers did. “When our language disappears,” he says, “so, too, do our stories, beliefs, and ways of seeing the world.”

Efforts are underway across the Philippines to save indigenous languages. Home to over 100 indigenous languages, the country holds cultures, histories, and worldviews under threat. Globalization, urban migration, and a strong emphasis on national languages like Tagalog and English have pushed most indigenous languages toward extinction. This is the story of the challenges of language preservation in the Philippines.

Although the Philippines has over 170 languages, only a few are indigenous. Centuries of colonization and policies prioritizing national languages have edged indigenous languages to the periphery. Today, only about 15 percent of Filipinos claim to be fluent ability in an indigenous language. If trends continue, the linguistic diversity that once flourished here may vanish within decades.

Lina Cruz, a government linguist, sees language preservation as daunting. “Official recognition is not enough,” she explains. “We need comprehensive support systems that ensure these languages are taught, spoken, and respected.” However, funding often limits government efforts, and the cultural divide between urban centers and indigenous communities means that most initiatives lack the resources needed to succeed.

Preserving Kankanaey is a cultural and personal duty for grassroots advocates like Alon. “When children learn Kankanaey, they don’t just learn words. They connect to the wisdom of generations,” he says. In Alon’s classroom, students learn to speak and understand traditional stories, rituals, and values embedded in the language. “It’s a way of seeing the world we cannot afford to lose.”

These efforts, however, face practical challenges. Younger generations, especially those moving to cities, often consider indigenous languages impractical. “There’s pressure to learn languages that create job opportunities,” says Felix Ocampo, who works for a nonprofit focused on cultural heritage preservation. “Our indigenous languages are less economically viable today, so many young people don’t prioritize them.”

This shift is painful for a language custodian like Elder Juan Dominguez, who speaks Kankanaey fluently. Juan describes his mother tongue as spiritually connected to the land and ancestors. “Our language is our soul,” he says. “If we lose it, we lose our roots. We lose who we are.”

Only a few programs can claim progress in revitalizing indigenous languages. Recently, a bilingual education program was introduced in select indigenous communities, incorporating native languages alongside Filipino and English in early education. This approach allows children to learn academic subjects in their mother tongue, connecting language to cultural knowledge.

Digital technology is also aiding preservation. New initiatives like online language databases and audio archives document endangered languages for future generations. These archives allow communities to record native speakers and capture vocabulary that might disappear.

The disappearance of a language signifies a profound cultural loss. Language is more than vocabulary; it represents identity, knowledge, and perspectives. If indigenous languages vanish, so will the ancestral wisdom and stories that give voice to everything from sustainable agriculture to local governance. For a linguistically rich country, the stakes are high.

As Alon says, “Our languages are like living roots, connecting us to the past and anchoring us in who we are today.” Without these roots, something irreparable is lost within communities. Yet, while the struggle to preserve indigenous languages continues, individuals like Alon and Juan remain hopeful. “We may be few,” Alon says, “but as long as one child still learns our language, there’s still hope.”

The fight to preserve language is a race against time. With every lesson taught in Kankanaey and every story shared in the native tongue, a piece of Filipino heritage is kept alive. For those dedicated to this cause, it’s not just about words—it’s about cultural survival, resilience, and a future where every Filipino can hold on to the echoes of their ancestry.