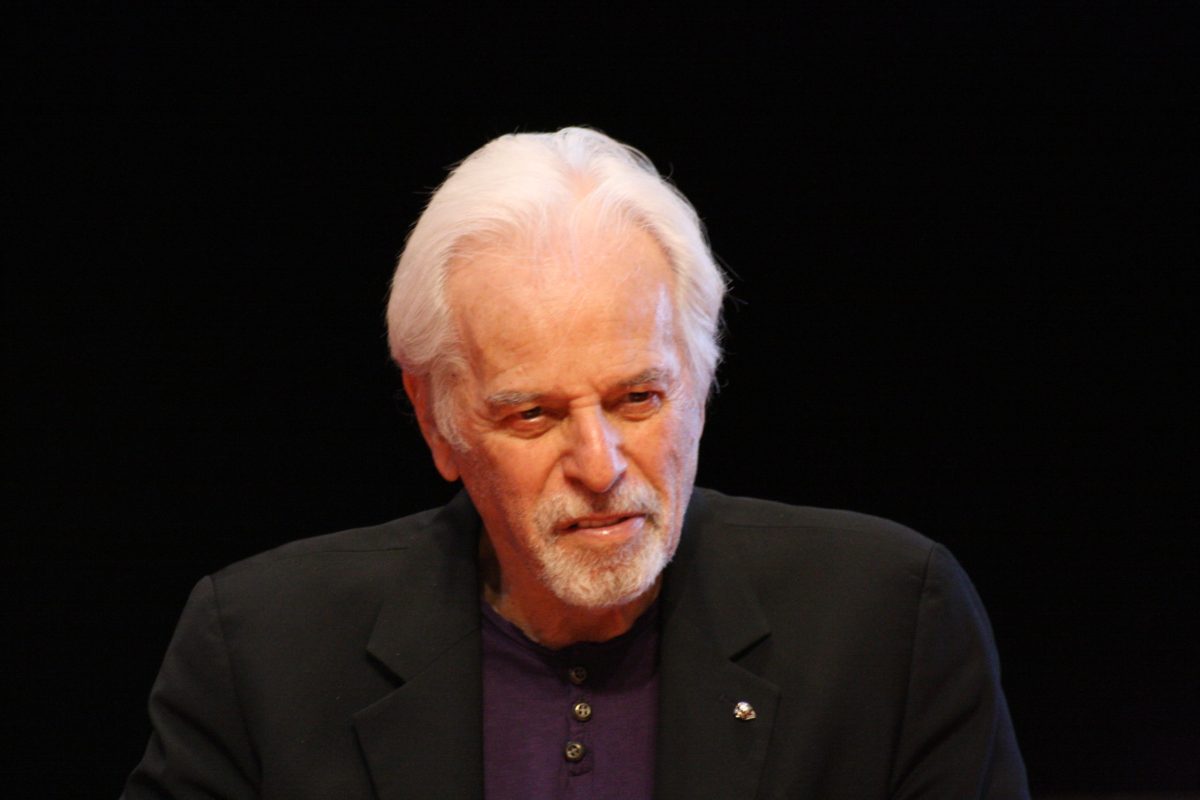

“The Flowers of St. Francis”, a visual treat from the director Roberto Rossellini, was an unexpected delight with a somber subject matter. Despite the presence of a renowned Catholic figure in the film’s title, it was pleasantly surprising to watch a film about faith without any fire and brimstone lecturing.

The film’s original title, “Francis, Jester of God”, is a more fitting and honest description. A series of vignettes woven together by the soul searching and whimsical happenings of a group of monks, the film may come across as Absurdist to some and spiritual to others. St. Francis is not even the main focus in all of these vignettes, despite the legion of monks seeking to apply his preaching to every aspect of their lives. At times the monks are bumbling about; gracing all those around them with beatific smiles, while simultaneously infuriating those outside their ranks by begging them to follow the ways of Jesus Christ. Francis and his followers find “true happiness” when a man throws them into the dirt and threatens to physically harm them for incessantly harping about praising the Lord. To the modern person, especially coming from a generation criticized for its addiction to instant gratification, this scene gives off a vaguely sadomasochistic vibe, since it isn’t really ingrained in present day culture to forgo pleasures or ease of way. Another scene, in which a monk cuts off a pig’s leg in an effort to feed another monk, contains a dark juxtaposition: the monk coos and happily attempts to coax “Brother Pig” to give up its leg for the greater good, and is followed by the horrible screams of the pig as he hacks off its leg. The monk emerges from a bush smiling and holding the sawed off leg; he later insists that the pig had been happy to give it up, which is quite hard to believe.

“The Flowers of St. Francis”, to me, is an almost Absurdist work. Attempting to fill their lives with meaning, the monks decide their lives must be led without any earthly temptations. In one vignette, a monk gives away even the habit on his back to a beggar, but refuses to be parted with his ricotta. The words of Giovanni, an addled and elderly man, are nonsensical at times and very Waiting for Godot; one particular scene even has him and all of the monks spinning in circles to imitate how children play.

The whimsical elements of the film, however, do not entirely overshadow the Christian message being explored by Rossellini. The director translated the transcendental teachings into the cinematography of the film, as the camera shots of the Italian countryside exude a sense of tranquility and peace beyond material greed and desire. True to Italian neorealism, Rossellini only used one actor for the film. The monks of “The Flowers of St. Francis” were actual monks from an Italian monastery. In a way, it could be said that Rossellini injected genuine Christian piety into his film without actors having to learn it.

The film has a childlike happiness to it, with the monks seeing the world as an enchanting land to spread the word of God, and all the better if they suffer while doing so. Rossellini, releasing this film in 1950, managed to carry the teachings of St. Francis beyond the 13th century. The nonreligious, those practicing another faith, and Christians alike could appreciate the rich textures and visual composition of the film without being overwhelmed by dogma.