You’ve come down with a case of gonorrhea. That’s unfortunate, but there are almost half a dozen antibiotics on the market designed to treat Neisseria gonnorrhoeae: penicillin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, cefixime, and ceftriaxone. The only problem is that the gonorrhea of the 1980s, when these drugs were first developed, is not the gonorrhea of today – and the gonorrhea of today is resistant to all but one treatment, with two strains identified as resistant to all antibiotics. It’s almost untreatable.

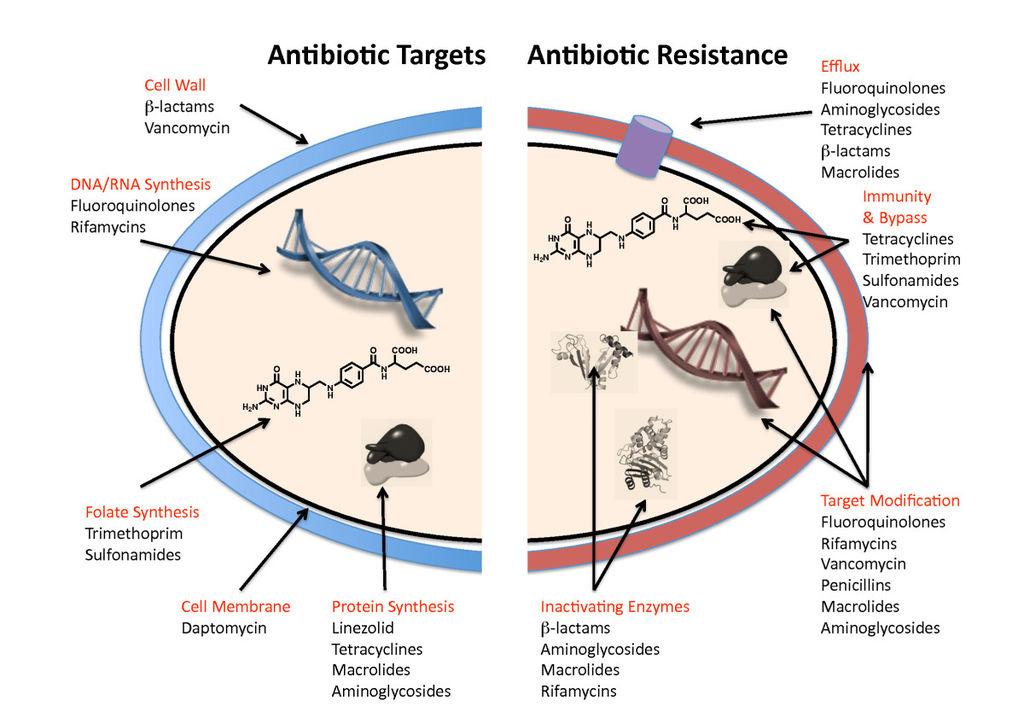

Drug-resistant bacteria are defined by mutations which increase their survivability against drugs which previously spelled doom for these microorganisms. A bacterium with high fitness is most likely to survive a dose of antibiotics, reproduce, and pass on its resistant genes to its offspring, thereby creating stronger and stronger individuals in the population. Over 200 variations of resistant bacteria have been identified in the United States, infecting 2 million and killing over 20,000 Americans per year, according to the Center for Disease Control. Studies suggest that antibiotic-resistant bacteria will be killing millions by 2050, and resulting in significant losses in agriculture, disaster preparedness, and economic production. So where are the new antibiotics?

Very few companies in pharmaceuticals are willing to invest capital into the research and development of antibiotics. Despite the rise of these so-called “superbugs”,including gonorrhea, tuberculosis, and salmonella, the market for antibiotics is simply too small to be profitable. Consider the cost of developing a drug: from formulations to quality control, to clinical trials to marketing, companies are often spending over $2 billion to produce a new treatment. For a product that consumers use for only 7-14 days at a time, this economic model just is not worth the investment.

As new bacterial isolates are developing drug resistance, many questions remain: how long will current treatments be effective? How long until deadly diseases like E. coli, syphilis, and meningitis,too,become untreatable? When will it be profitableto treat patients with resistant conditions? Who is going to pay for decades’ worth of research and testing, especially when developments fail much more frequently than they succeed?

It’s impossible to entertain definitive answers for these questions, but scientists in the meantime are brainstorming methods to slow down the spread of antibiotic resistance. Some suggest government subsidies or incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to develop new drugs, but the easiest way to treat bacterial resistance is to prevent it. This generally means limiting the misuse of antibiotics, which includes improved diagnostic methods for healthcare professionals (such that antibiotics are not prescribed for non-bacterial infections) and more comprehensive patient education to ensure full adherence to prescriptions.

The World Health Organization cautions that a global approach is necessary to prevent the loss of the most important drug class in the history of medicine, but the current prognosis for this epidemic left untreated is bleak. So imagine this: You’ve come down with a case of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea. That’s unfortunate, but you won’t bring in enough profit to justify the expenditure on new research and development. In addition to being uncomfortable and inconvenient, this infection now runs the risk of killing you. And you’re fresh out of antibiotics.

Photo credits: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/figures/1741-7007-8-123-1-1.jpg Antibiotic targets and mechanisms of resistance. See text for details.