During Women’s History Month, we tend read empowering pieces about historical feminists, modern trailblazing women, and important cases where the glass ceiling has been shattered or raised. In this piece, however, I want to dive into the past and analyze an often-overlooked piece of feminist history: the phenomenon of witchcraft in Europe and its colonies and the role that witchcraft and magic played for women in those societies.

As European history progressed and the Protestant Reformation took hold on the continent, the Roman Catholic Church and other religious organizations became very concerned with stopping the threats of ‘heresy’ and ‘black magic’, which they saw as a threat to their power and the souls of the people.

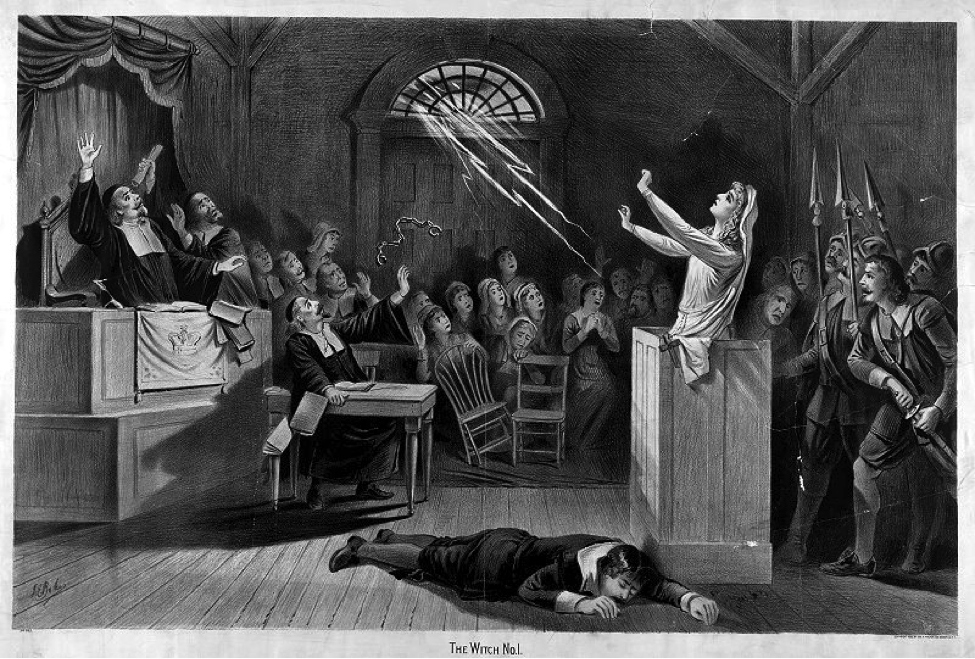

This sparked the witch trials, made famous in America by those held in Salem, Mass. around the 1690s. Witch-panic persisted for far longer than those events alone, however, and lasted from about 1490 until the latest trials in 1750.

Wolfgang Behringer, a German historian specializing in witchcraft beliefs of early Modern Europe, estimates that as many as 60,000 people were executed for witchcraft over this period. To us in modern times, the number seems unbelievable. But in these centuries, beliefin magic was an essential part of life, and the Church used that belief to terrible effect.

So, what exactly is a witch? Like the nature of magic itself, this question is a source of much debate.

It seems clear that everyone who practices magic was historically not considered a witch. Witchcraft seems to specifically refer to those who practiced magic on the fringes; those who made others uncomfortable; those living alone and rumored to be able to do great and terrible things.

Throughout the history of Europe, witches filled various and oftentimes opposing societal roles. They were sought out for solutions to problems that could not be solved, like bad harvests and sickness, and were also treated as healers and wise-people. In England, they were referred to as ‘cunning folk’ and were treated with a kind of awe.

However, they also served the role of feared scapegoats for all problems. If cattle died or a famine struck, the witch was blamed. If a baby fell sick and died, the witch was blamed. Still, the witches fulfilled many necessary functions. They were the only recourse for the marginalized in society, especially women.

Women in European society were not granted the same privileges as men. Their roles were restricted, and their value was tied to their ability to bear children. For those who could not or did not want to do so, witchcraft provided a means of taking charge of their destiny.

Because magic was so widely revered, witches, as users of it, were powerful in ways women were typically never otherwise able to be. They were also able to offer help to other women in need. They would provide folk recipes to abort fetuses, attract husbands for women (and thus financial and societal stability), and enact revenge against those who wronged women.

Witchcraft thus has clear feminist implications. While not all witches were women, 75-85% of those killed in the witch trials were female, according to Anne Barstow’s “Witchcraze”. They were the most likely to be suspected, since women were considered sinful and distrustful by religion at the time and many did not fit the narrow expectations set by society. Therefore, the archetype of the witch was disproportionately associated with women and witches were uniquely poised to help women with issues we would consider feminist today: reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, financial autonomy, and equal balance of power.

In some ways, witches by their very nature represented a subversion of the patriarchal power system. Since they wielded ‘magic’, they had power in the minds of the people, but their power did not operate by the patriarchal rules and laws of the time. It existed outside society and allowed women and other marginalized people to claim power and autonomy through their own merits.

In our current era of #MeToo and the Women’s March, we tend to focus on more recent figures for inspiration and knowledge. But amongst all the relevant discussions of modern powerful women and feminist heroes, we should still remember the historical power of the archetype of the witch, and its role even today.

So this Women’s History Month, put on your pointy hat, brew some tea, and think about just how far we’ve come.

Photo: The Witch No. 1 by Joseph E. Baker from c. 1892