We have reached a point in society and the media where climate change is at the forefront of our lives. Rising temperatures, ocean pollution, and the petroleum industry are constantly being portrayed as the big bad environmental villains, so much so that we forget about the more stylish environmental killer: fast fashion. According to The Fashion Law’s website, this consists of “rapidly translating high fashion design trends into low-priced garments and accessories by mass-market retailers at low costs.”

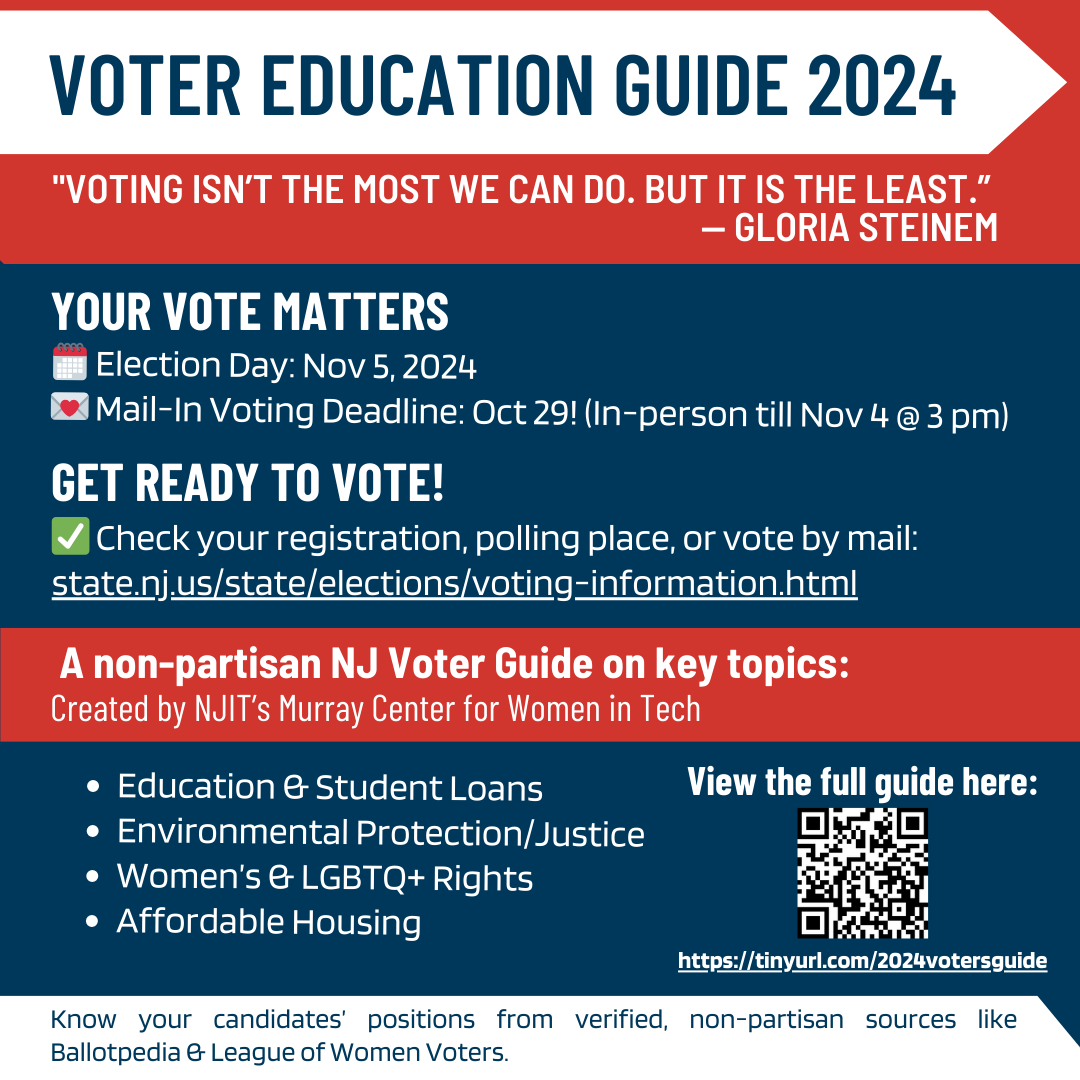

This year’s Women Designing the Future Conference, organized by NJIT’s Murray Center for Women in Technology, offered an action-oriented approach to addressing environmental issues, including those created by the fashion industry.

“Fast fashion is one of the worst environmental pollutants, so just getting that information out there, and making people realize that it is something that’s really bad for the environment” is a priority, Murray Center Coordinator Tara Walenczyk said.

The fashion production industry is responsible for a total of 10% of global carbon emissions. To produce the average t-shirt, 2700 liters of water are used, along with an incredible amount of chemicals, pesticides, and harmful dyes that are often released into rivers and oceans as toxic wastewater. After the production comes the delivery by ships, trains, and trucks. The carbon footprint of cotton is enormous, according to “The Life Cycle of a T-shirt”, a TED-Ed video shown during the conference.

“The clothing industry is the number two polluter in the world, second only to fossil fuel,” said Fran Sears, the Special Projects Manager of the Murray Center. “And I don’t think any of us really realized that until we started thinking about doing the clothing swap.”

Many companies rely heavily on the fast fashion business model of designing, producing, delivering, wearing, and throwing out clothing fast. Famous examples include Shien, Zappos, and Romwe. These companies are known for their low prices and low quality.

However, for most young people who are unaware of the fashion industry’s impact on the environment, those low prices are incredibly appealing, and so the companies’ products sell out fast. Thus, our response to this environmental crisis must also be fast.

At the conference’s clothing swap, event participants were encouraged to bring any articles of clothing that they were willing to part with, and swap with other participants. Even the simple process of picking out items to swap opened the eyes of many participants to the true extent of the waste that fashion produces.

“I was cleaning out my closet, and I found so many things that I didn’t want to wear anymore, but I just have them,” first-year Computer Science major and student ambassador for the Murray Center, Hiba-UR-Rahman Khalid said. “It makes me more careful when I buy clothes now.”

Other participants already avoided fast fashion, and for them, the clothing swap reaffirmed their beliefs.

“I started watching YouTube videos that talk about the fashion industry designers and all that, and I landed on the environmental side of it,” third-year human computer interactions major Sarah Huezo recalled. “I had so much information on my hands that I couldn’t not do anything with it. It felt like it was ethically my responsibility to at least avoid contributing to all these disasters.”

Thrifting, clothing swaps, and reusing and mending old clothes are all simple, cheap, and viable ways to fight fast fashion. And sporting thrifted finds and mended clothing presents opportunities to educate others on the issue of fast fashion.

For Huezo, these solutions not only help the environment, but they put to rest her own guilt over consumer habits. “I feel at ease,” Huezo said as she participated in the clothing swap. “I feel like I’m at least doing a little something to make a difference. Even though it’s not a lot, it’s still enough for me.”

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory (www.civicstory.org) and the NJ Sustainability Reporting project (www.SRhub.org).